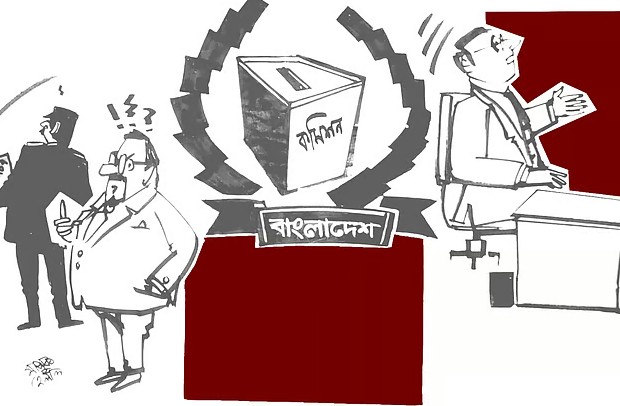

A flurry of developments is taking place ahead of the upcoming national election. Although political polarisation has not yet taken a definitive shape, efforts are underway to form an electoral alliance centring on the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Jamaat-e-Islami.

Some parties, meanwhile, are keeping all options open, opting for tactical flexibility over ideological clarity, a reflection of the current trend in politics where strategy often outweighs principle. Jamaat ameer Shafiqur Rahman’s apology for all events since 1947 and BNP acting chairman Tarique Rahman’s pledge to form a post-election national government are both part of this broader strategic game.

Before the legal framework for the July Charter is finalised, the interim government’s advisory council approved the election commission’s proposed amendments to the Representation of the People Order (RPO) on Thursday. In principle, many of these amendments deserve support, such as requiring candidates to disclose their domestic and foreign income and assets, cancelling polls in constituencies with serious irregularities, barring fugitives from contesting, and mandating that donations above Tk 50,000 be made through banking channels.

These provisions are likely to enhance transparency and accountability in the electoral process.

However, the mere filing of a charge sheet does not make one guilty. Whether an accused is guilty or innocent is for the courts to decide — not the election commission or the government.

Raising the security deposit for candidates from Tk 20,000 to Tk 50,000 seems unjustified. It risks excluding those with limited financial means from participating in elections. Has the election commission assumed that all candidates must be wealthy?

The most controversial and widely criticised amendment is the provision that even if a party contests as part of an alliance, its candidates must still use the party’s own electoral symbol. By enforcing such a rule, the Commission appears to intrude upon both individual freedom and collective political strategy. Let’s recall a few examples from history: in 1954, the Jukto Front coalition contested under the boat symbol; in 2001, the BNP-led alliance — comprising BNP, a faction of the Jatiya Party, Jamaat-e-Islami, and Islami Oikya Jote — used multiple symbols across parties. Similarly, in 2008, the Awami League–led Grand Alliance fielded candidates under both the boat and the plough. Even in 2018, Jamaat and several unregistered allies of the BNP contested under the “paddy sheaf” without issue. Why, then, should this suddenly become a problem?

Jamaat contested the election under the “sheaf of paddy” as the party did not have registration at that time. Will any political party unregistered with the election commission not get any electoral symbol in the election if it forms an alliance with any registered party in the coming election?

BNP has objections against inclusion of such a rule. The party’s standing committee member Salahuddin Ahmed told Prothom Alo yesterday that they strongly oppose this amendment: “Under Section 21 of the RPO, registered parties in an alliance could previously contest under any ally’s symbol. We proposed retaining that clause. If it’s scrapped, we won’t accept it.”

Jamaat, however, holds the opposite view. The party’s nayeb-e-ameer Syed Abdullah Mohammad Taher told Prothom Alo, “Every party has its own identity, and its symbol represents that. So, it’s better for registered parties to contest under their own symbol.”

Let the allied parties themselves, as in the past, decide what is most appropriate for them.

The recent amendment to the International Crimes Tribunal Act adds another layer of complexity. It stipulates that anyone formally charged with crimes against humanity cannot contest national or local elections.

Trials under this law are ongoing against several former leaders of the Awami League (whose activities have been banned), accused of involvement in killings during the July 2024 uprising. Many senior leaders, including former ministers and MPs, remain in hiding, facing charges ranging from murder and attempted murder to corruption.

The approved RPO draft also broadens the definition of “law enforcement agencies” to include the army, navy, and air force — meaning military personnel can now be deployed at polling stations alongside the police, without the need for separate orders.

This raises both practical and legal questions. The recent case against 15 serving army officers stemmed not from dereliction of duty within the military but from alleged human rights abuses during their deployment in civil operations. Elections, too, are a civil affair. If any member of the armed forces becomes involved in irregularities during election duties, will they then be tried under civilian law?

The army’s constitutional role is to defend the nation’s sovereignty and protect against external threats. Deploying them for internal law enforcement inevitably invites controversy.

Yet the current law and order situation leaves the interim government with few alternatives if it wishes to hold a free and fair election. Still, ensuring the neutrality and professionalism of the armed forces during this process is vital. Ideally, Bangladesh should be able to conduct elections without relying on the military for law enforcement. While that may not be possible this time, policymakers must ensure that future elections can proceed without requiring such deployment.

Courtesy: Prothom Alo Online