WHAT are workers? Are they human beings? Do they have only a bundle of muscles but, no brains? How do they feel and how do they think? Do they think at all? What do they face in their life — in factories, in foundries and other shops, in assembly lines, in unions?

Workers’ answers to the questions above differ from the response the workers’ masters present. The factor that draws the delineating line is, in short, class position, which is often blurred while discussing issues of life and work, be it related to workplace or economic program, politics or social initiatives, charity, cooperative, ideology or culture.

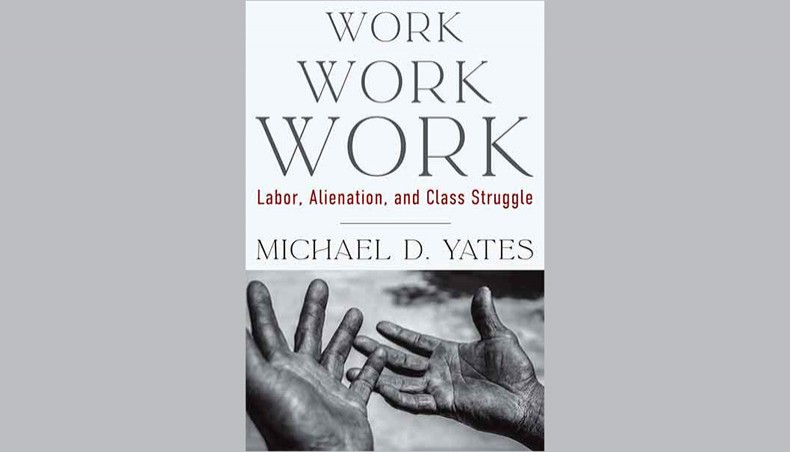

Michael D Yates, a labour organiser, discusses this issue in Chapter 1, ‘Take this job and…’ of his recently released book Work Work Work: Labor, Alienation, and Class Struggle (Monthly Review Press, New York, 2022). The professor of labour economics begins the chapter with a statement, simple or complicated:

‘It would be astonishing if the more than 150 million child labourers in the world were happily employed. Or if the 800 million farmworkers globally were content with their circumstances.’

The mainstream investigates: Child labourers’ happiness with employment? Isn’t it an invalid question? The system takes away happiness of childhood from millions of children, and then, searches whether or not the child workers are happy? The system shackles millions of farmworkers into bondage, and then, searches whether or not the farmworkers are happy? The system enslaves millions of workers into a life without humane condition, and then, surveys whether or not the workers are content with their life? Isn’t it a mockery by the system and its scholarship? Isn’t it a crude trick to hide the system’s cruelty and its scholarship’s identity — in the payroll of the system?

Michael Yates tells about two workers: his father and Ben Hamper, author of Rivethead: Tales from the Assembly Line (Warner Books, New York, 1991): ‘Both spent good portions of their lives as factory workers, my father in a glassworks and Ben Hamper in an auto plant.’

The description goes further: ‘Both became factory workers because it was almost predetermined that they would. All their relatives and friends were factory hands.’

‘Predetermined’ — the powerful process or factor that determines the lives of millions of toilers in the world system of exploitation! Workers’ fate is sealed forever, and for perpetuity in the system, if the system does not get overthrown. This is eulogised, philosophised, rationalised, ideologised. Who rationalises this? The philosophers defending the system, the scholars serving the system, the interests thriving on exploitation do this job. How is this rationalised? With illogic, by imposing the formula – never question, by creating a premise that stands on void, by ignoring struggle between classes, by denouncing the role of force in society’s historical journey, and by condemning the use of force by the exploited, although the system has established and keeps on sustaining its interests by force.

The author cites Ben: ‘Right from the outset, when the call went out for shoprats, my ancestors responded in almost Pavlovian compliance.’

What a tragedy in human life — Pavlovian compliance! But this tragedy was not only of Ben’s ancestors; it is of all tied to the system of exploitation: comply, always comply, never question, never even dream to question, never defy, never be disloyal and disobedient, never be critical, never think over the role of force in historical journey of humanity, and denounce whoever proposes to raise questions, whoever brings to notice class rule and the role of force in class rule. And, this tragedy was neither created nor called by these people. The system of exploitation creates this tragedy, and it imposes on humans, as Ben narrates: ‘Drudgery piled atop drudgery. Cigarette to cigarette. Decades rolling through the rafters, bones turning to dust, stubborn clocks gagging down flesh, […] wars blinking on and off, thunderstorms muttering the alphabet, crows on power lines asleep or dead, that mechanical octopus squirming against nothing, nothing, nothingness.’ Yates’s father was ‘a glass examiner; he checked glass plates for flaws under high-intensity lights. Four cutters, working on incentives, depended on him for plates, and they were not happy if he was too slow. The boss was not happy if he was too careful. He coped with the stress by taking aspirin and smoking, several cigarettes burning simultaneously.’ It’s the story of all workers — in different forms, in different places, with different speeds and stress.

What happens then? Yates writes: ‘[Y]ou can almost feel what it does to people. Some become zombies, […] or the man who answers “same old thing” no matter what you say to him. Not a few crack up completely; […] A few workers become so habituated to the line that they hate to leave it, like the pensioners who sat in the park in my hometown wistfully staring at the plant gate across the street.’ A dehumanising upshot! Souls, irrespective of blue or white collar, reach at this point: they hate to leave the machine that exploited them, that made them part of the machine, that compelled them to think as the machine dictated, they deny to question the machine and the machine’s process, they deny to define life and issues of life in some other way than the definitions the machine defines. It is ‘staring at plant gate.’ The plant, the machine appears a mirror of joy and happiness. A triumph of the machine!

Do the brains, the muscles sold, compelled to sale, to the system turn satisfied? A sort of satisfaction reins in a part of the brains and muscles. What sort of satisfaction is that? The author of Work Work Work, who also taught union workers for years, writes: ‘[S]atisfied compared to what? The lack of a job? An unknown alternative?’ These are issues: compared to something, lack of or a lower-paying job or an unknown uncertainty. A bonus, an increase in wages, a promotion, a capacity to buy better clothes or food for daughter or son once or twice annually, a loan to buy a refrigerator or a car — these drive the indicator of satisfaction high. Is it a slave’s satisfaction — lifelong allegiance and obedience to the master, remain slave, in exchange of a better food and less or no flogging?

A mostly ignored fact is told by Ben that Yates refers to: Gulag City — a ‘Japanese-style’ plant.

The mainstream scholarship and propaganda machine doggedly ignore the following facts: (1) capitalist system, which at times turns Gulag; and (2) persistent brutality of the system, which ceaselessly murders many over a long period of time, in addition to keeping millions in cages. The murder at mass scale (1) is not visible all the time, (2) is explained in some other way, (3) is attributed to other phenomena, and (4) is defined in isolated way. This murder is not accidents during the production process, which puts extra weight to the business of the murdering-system. The propaganda also depicts a rosy picture of certain labour management systems by hiding the inner-working of the system that efficiently hides its fangs — keep the workforce tamed and intensify exploitation. Instead, stories on the Soviet Gulag are persistently propagated.

Michael Yates, regularly representing unions at bargaining tables, writes a burning fact, which is overlooked or ignored by all the rightist ideologists, all the philanthropists, many union leaders, many NGOs involved with labour activism, and a good number of ‘radicals’: ‘[W]ork itself, no matter how oppressive, does not engender class consciousness and solidarity. It is more likely to lead to such poor health and mental stress that coherent thoughts and actions are difficult.’

First, the mechanism takes away the capacity to think — a dehumanising process. Is it not murder, murder of existence as human? Whatever remains there is incoherence — tongue-tied thoughts, actions without meaningful connections, undisciplined actions. The exploiters like it and love it. It takes away that capacity, which is essential to make radical change of the dehumanising system.

Yates, as an example, refers to historians David Montgomery and Jeremy Brecher, and his father.

Montgomery and Brecher wrote: ‘[W]orkers eagerly debated great questions during the many mass strikes before the Second World War. Who should run the factories? Who should lead the nation?’

His father told him: ‘[A]fter the war, his factory was alive with talk of politics.’

Today, what’s happening? Yates writes: ‘[M]eaningful discussions are far outnumbered by talk of booze, sex, sports, and hunting.’

It is not a scene only from the Uncle Sam-economy. In other societies dominated by exploiters, it is basically the same also: Difficult to find workers talking about their politics and democracy, and organisations for radical change, not the exploiters’ politics, democracy and organisation. The problem is not with the workers.

The problem begins at two levels: at the work mechanism, and with those that have usurped leadership. A part of the leadership has been deployed by the system with this particular assignment — let the workers get confused and forget their essential issues – while the rest is unaware and incapable, which is also the system’s capacity to keep that part crippled in terms of idea and thought.

Are the exploiters not happy with this realty? They are.

With this reality, Yates tells the urgent and inescapable fact: ‘[T]here is more work to be done than radicals might think.’

No doubt, more elementary and basic work, which may appear small and insignificant to somebody, to be done. Re-raising and re-debating “old” questions, including workers’ politics and political power, are essential. Imperialist agencies are active in the area of the workers’ movement. It’s a comparatively new development. Collaborationist big unions from the global metropolis organise unions in the southern hemisphere and influence workers’ movement in countries in the South. A group of labour organisers are picked up and mobilised as bargaining chips by capitals abroad. ‘Labour’ organisations are floated to further imperialist agenda, and to blunt workers’ class consciousness. These issues/practices/trends go un-discussed in the circles claiming to be radical, although these are to be exposed and nullified immediately.

There is further bitter fact told by Yates:

‘[U]nions, as currently constituted, offer working people a very partial victory. [….] In the old plants, the union made it hard to fire workers and made it possible for them to resist and sometimes to defeat the worst management abuses. But since the radicals were expelled long ago, it has not stood for anything except higher pay and some job security, and today it cannot deliver these. In the newer plants,it is firmly in bed with the companies, pushing the labour-management cooperation schemes […]’

This is not only a snapshot from a single land. A deeper and wider search in lands will find this: major unions in bed with companies — a capitulation to capital, a sellout of workers’ position, a giving up of proletarian interest. It is a major problem being faced by unions upholding workers’ interests.

This brings back a few of the questions related to unions that Lenin raised while struggling to organise a radical workers’ movement in Russia. The Orthodox priest, Georgy Gapon (a supposed leader of workers later discovered to have been a police agent) was not the only problem in the workers’ movement in Russia. That was a particular problem at a particular time there. Even, prior to the employment of Gapon by the Tsarist police, Lenin had to resolve other union-related issues. Otherwise, it was difficult to move forward for building up the workers’ political power in Russia. Many union organisers mostly ignore these issues and deny learning lessons from this episode of revolutionary workers’ movement.

This chapter, a review of Ben Hamper’s book Rivethead: Tales from the Assembly Line, reminds us of the bitter parts of the reality with a tone of criticism of Ben: ‘[F]ailure, even unwillingness, to push his class consciousness forward.’

With a mild tone, Yates presents an answer: ‘Maybe it is too painful to do so. Maybe the unions have failed so utterly to create a working-class ideology that would force workers to ask the right questions and struggle toward […] a new world.’

Here, comes the question of class consciousness, which is brushed out by those in the service of capital, as class consciousness denies all authorities capital creates to carry on its rule.

The author has a more bitter tone: ‘No doubt radicals have failed workers too, either ignoring them for the pleasures of theoretical debate or trying to become one of them so hard that they forgot that work in this society destroys the human spirit.’

Pleasure of theoretical debate at the cost of abandoning workers! Undeniable fact overwhelmingly found around. It sounds spiritual, but it is the reality: Work in this society destroys human spirit. This reality remains behind the eyes of a group of ‘emancipators’ while they search saach, true, path to emancipation.

Yates proposes: ‘If we are ever to liberate ourselves, we must reinvent work.”

Liberation of ours is a fundamental question in the life of humanity, and reinventing work is a complicated task. Therefore, there comes the questions: How to reinvent work, and from where to begin the task of reinvention? Humanity’s journey is for liberation, liberation from all forms of bondage. It is going on for ages, and it has to march forward.

The consequence of a failure to reinvent sounds like a dire warning from the author, as he writes: ‘Either we will convert the daily hell that is work today into something that connects us to other people and the world around us, or we will descend further into the alienation engulfing us.’

‘But where is the way out?’ With this question, Michael Yates concludes the chapter.

Probably, the author gives a space to readers to search for an answer to the question. Or, it is a reflection of an overwhelmingly hostile reality, a capital-scape where exploiters’ standard flutters.

But, to dissect dialectically, there is an opposite action moving on. It is in the class struggle-scape. The way out begins with a scientific approach to find out the roots of failure, and the Vaporyod, forward. The way out is to begin by taking stock of the existing condition, immediately initiate work with a scientific approach, expose appeasements and sellouts, gain momentum, and be stubborn and defiant.

Farooque Chowdhury writes from Dhaka. One of Farooque’s recent books is The Great October Revolution (Dhaka, 2022). Farooque Chowdhury thanks Michael D Yates for editing of this article.